Sit back, grab a glass, and let me tell you the tale of an old barley farmer from a small village in Scotland.

Every summer, when the grains go yellow and start nodding towards the soil, he grips his gnarled walking stick, pushes to his feet, and trundles out to the fields with a groan and a huff.

There, just as he’s done for the past 40 years – and just as his father and grandfather did before him – he bites into a golden grain of barley to feel the crack between his teeth.

It’s ready for the harvest. Time to swath it, thresh it, and deliver it to the old malt master in the distillery across the village.

A good man, the malt master. He knew his father’s da. And he can tell from the smell alone whether the barley’s ready to be spread out on the cool stones of the malthouse floor. Less than two weeks and it will be off to the tun room for mashing.

Sounds nice, right?

Except it’s all a load of bollocks. Not on the farmers’ side, mind you. They know their craft and do damn hard work. And they deserve all the respect in the world for it. But the idea that execs at some massive multinational distillery have ever taken the time to shake hands with a small-time farmer is laughable.

There are over 130 whisky distilleries in Scotland, and only 10 of them actually malt their own barley. Oddly enough, for a land rich in one of the world’s most ancient strains of barley, a significant amount of the malt doesn’t even come from Scotland. It comes from a single outfit called Simpsons Malt down in England. Simpsons alone produces 235,000 tons of malted barley every year (the same total output of all of Scotland’s commercial malt houses combined), and most of it goes to scotch whisky distilleries.

Look, we love our scotch. But let’s be honest here: despite what their marketing teams say, most distilleries don’t see barley as anything more than a pile of starch that they can convert into fermentable sugar. There’s making whisky and there’s branding it, and with a few exceptions we know where their priorities lie.

There’s a lot of nonsense in the way whisky is marketed. And that’s on purpose because what’s being sold isn’t just alcohol for consumption. It’s a story, a heritage. This narrative informs the brand experience, and people tend to enjoy something more when it comes from a perceived tradition of craftsmanship. And, of course, they’re willing to pay more for it.

We recognize this, but at the end of the day we’re more interested in sharing what really makes whisky great without blowing smoke up people’s pot stills. We believe that most folks will enjoy their whisky more when true craftsmanship is part of what they’re consuming, which brings us to the subject of barley and how outsourced malting is a huge lost opportunity.

A quick refresher on how whisky is made

(For some of the hardcore whisky buffs out there, you can skip over this part. Although there may be some sciency tidbits that you didn’t know before. Or not. Either way, we aren’t passing up on an opportunity to geek out over whisky science.)

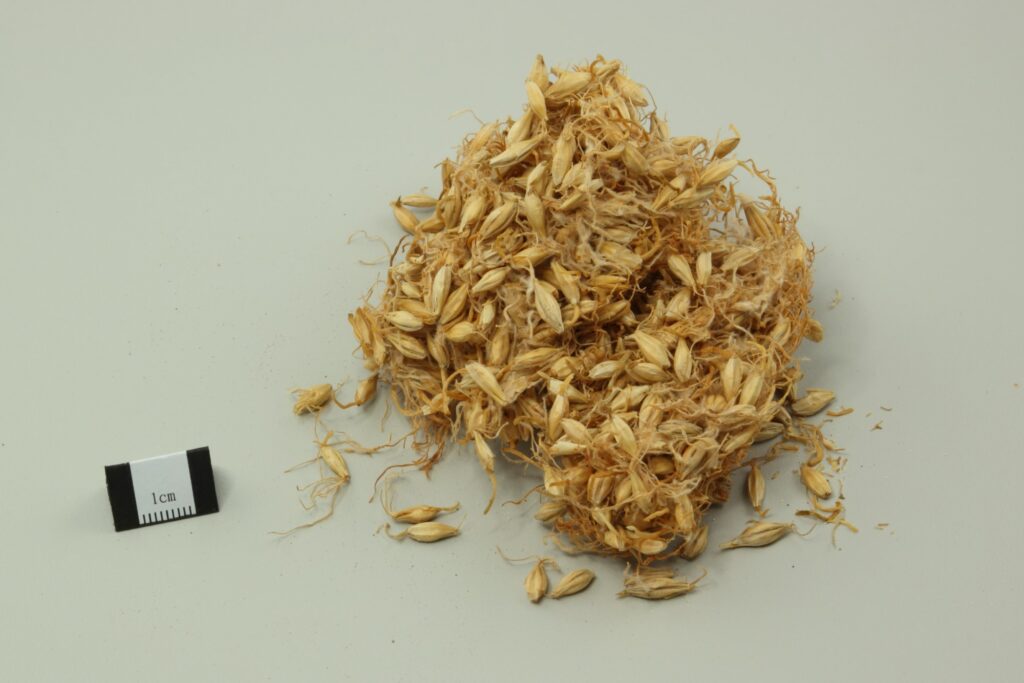

To start with, you get yourself some grains – usually barley – and you malt them. It sounds fancy, but to malt grains all you have to do is soak them, drain them off, and then spread them out in a controlled environment so they can germinate. This is traditionally done on a malt room floor.

The whole process usually takes about 7 to 10 days, which is one of the reasons why barley has been the grain of choice for making scotch for hundreds of years. It’s cheap, it’s one of the very few grains that actually grow in Scotland, and it can reliably sprout in a short amount of time.

You malt barley to create an enzyme called amylase, which is what helps break down starch into sugar. You need this sugar to feed the yeast, who perform their fermenty magic (official science word) and give you the gift of booze.

Fun fact: You have amylase in your saliva, and early fermentation was likely discovered by people chewing on grains and then spitting them out. In Latin America, they still have a fermented corn beer called chica that’s traditionally made by chewing on ground up maize to break down the starches into malt sugars. Chica chewing is an actual job, and yes we’re accepting applications.

(No, we’re not.)

Back to whisky. Once you have your malted barley, you ground it into a rough flour, add hot water to the mix, and dump it into a giant wooden vat called a mash tun. The water and heat activate the amylase, which breaks down the starches into simple sugars. You then pop this into something called a washback and let it ferment for about 50 hours, which gives you a type of sugary beer called, well, the wash.

You run the wash through a couple of stills to create new make whisky, then let it sit around in wooden casks and get sipped at by pesky angels for three or more years until you have yourself some whisky. (Yes, it’s two years in some places, we know. Please don’t hate-tweet us.)

So that’s how it’s made. Now let’s talk about what this all means when it comes to flavor.

Scotch mist

To be honest, not much. There’s very little difference in process from one distillery to another. This is one of the reasons why folks who are new to whisky tend to think that all whiskies taste the same. Because they kinda do at first, and that’s a symptom of overly streamlined, industrial production processes.

We can’t compete with that. And most importantly, we don’t want to, so we spent a lot of time breaking down the production process and figuring out which steps – if any – actually have a perceptible influence on the final product.

We realized that the entire scotch industry is pretty much built on scotch mist. There are some things you can do with your grains, stills, and casks that give you more granular control over the flavour profile and defining characteristics of your whisky. But out of expediency, or out of an almost rabid drive to cut costs and maximize profits, most distilleries don’t to these things.

Some say they do but don’t. We, on the other hand, will.

Beyond branding, why barley is actually important

Starting with barley, we will source our own grains directly from farmers with whom we have direct working relationships. We want to know exactly where our barley is coming from and what went into growing it. We will also malt it in house, dry it in house, and maintain complete control of every single step in the malting process.

We’re doing this for three reasons.

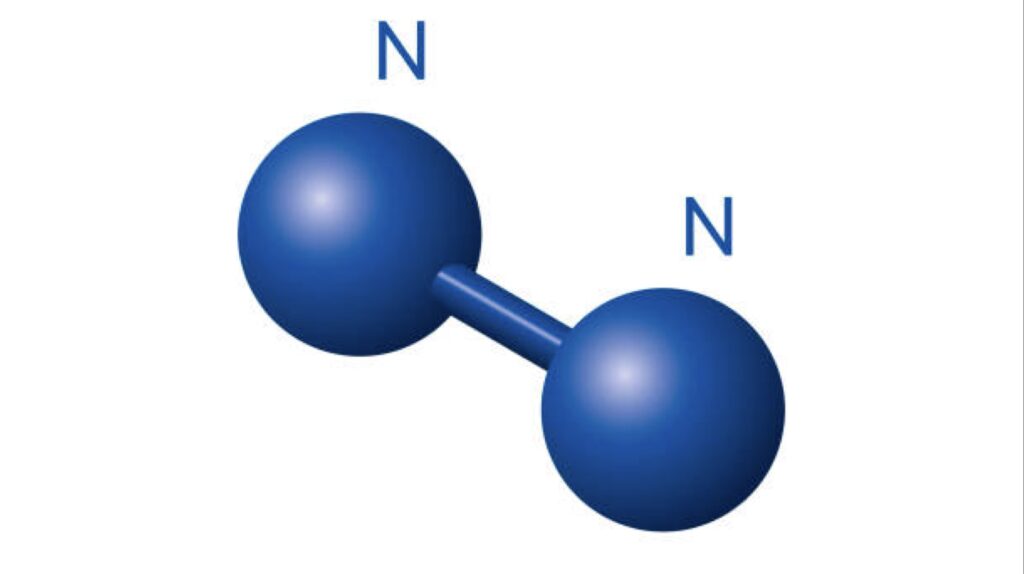

The first is out of sheer practicality. If we don’t have complete visibility into the prominence of our grains, we run the risk of nasties like nitrogen messing up our mash. Excess nitrogen from pesticides can lead to high grain protein levels, which can cause issues during fermentation and hazing in the final product. (Think floaties, blech.)

The second is to make our whisky tasty, but not for the reason you might think. Malted barley doesn’t taste like much, so it does jack all for the taste profile of a whisky – especially after the wash is distilled.

What imparts more flavour is roasting barley, or at least a portion of it. Roasting kills the enzymes in the grains, so you malt some and roast the rest, and then combine them for something that’s both tasty and fermentable. These are flavours that can be carried through to the end of the distillation process.

If you’re buying your grains in bulk, you have little control over this mix, nor of roasting times, quality of the grains, moisture levels, etc. So in our view it’s a lost opportunity.

And finally, we want something to share with you. Roasting, malting, and milling barley is a key part of traditional whisky craft, and we want to share that with everyone who visits our distillery. Just as stories inform experience, so does knowledge, and we want to build a distillery that’s both engaging and instructive to visit.

We want you to see and understand we’re doing absolutely everything we can to ensure that what we craft is the best of the best.

Ask yourself this: at the end of the day, do you want something that’s crafted blindly from bulk sacks of grain, sourced from a massive industrial malt house? Or do you want to know who the grains came from and why, and what decisions went into malting and roasting them by hand?

We know which one we want, which is why we’re doing this in the first place.

Would You Like To Read More?

If you enjoyed reading this, and you would like to catch up with some of our past articles, then please CLICK HERE and go to our News Section, where most of our other content is published.

Follow Us

If you have enjoyed reading this and want to learn more about Nine Rivers Distillery, then use the QR Code below to follow our WeChat Official Account.

Alternatively, if you prefer Linked In then you can CLICK HERE to follow us.

Facebook users, you can CLICK HERE.